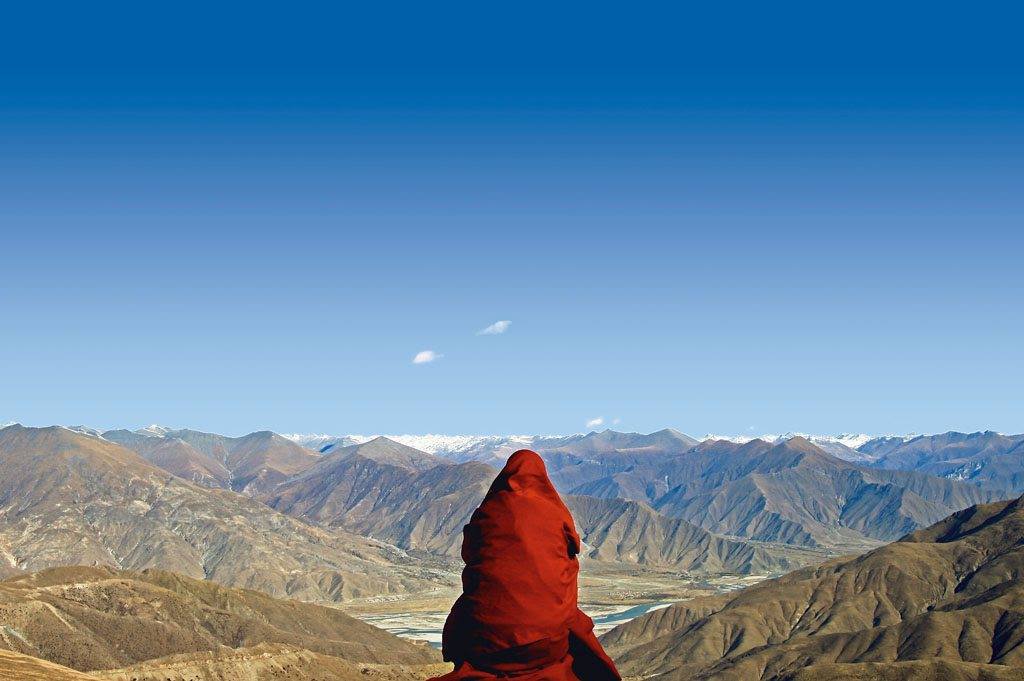

There are two kinds of refuge, says Mingyur Rinpoche—outer and inner. The reason we take refuge in the outer forms of enlightenment is so that we may find the buddha within.

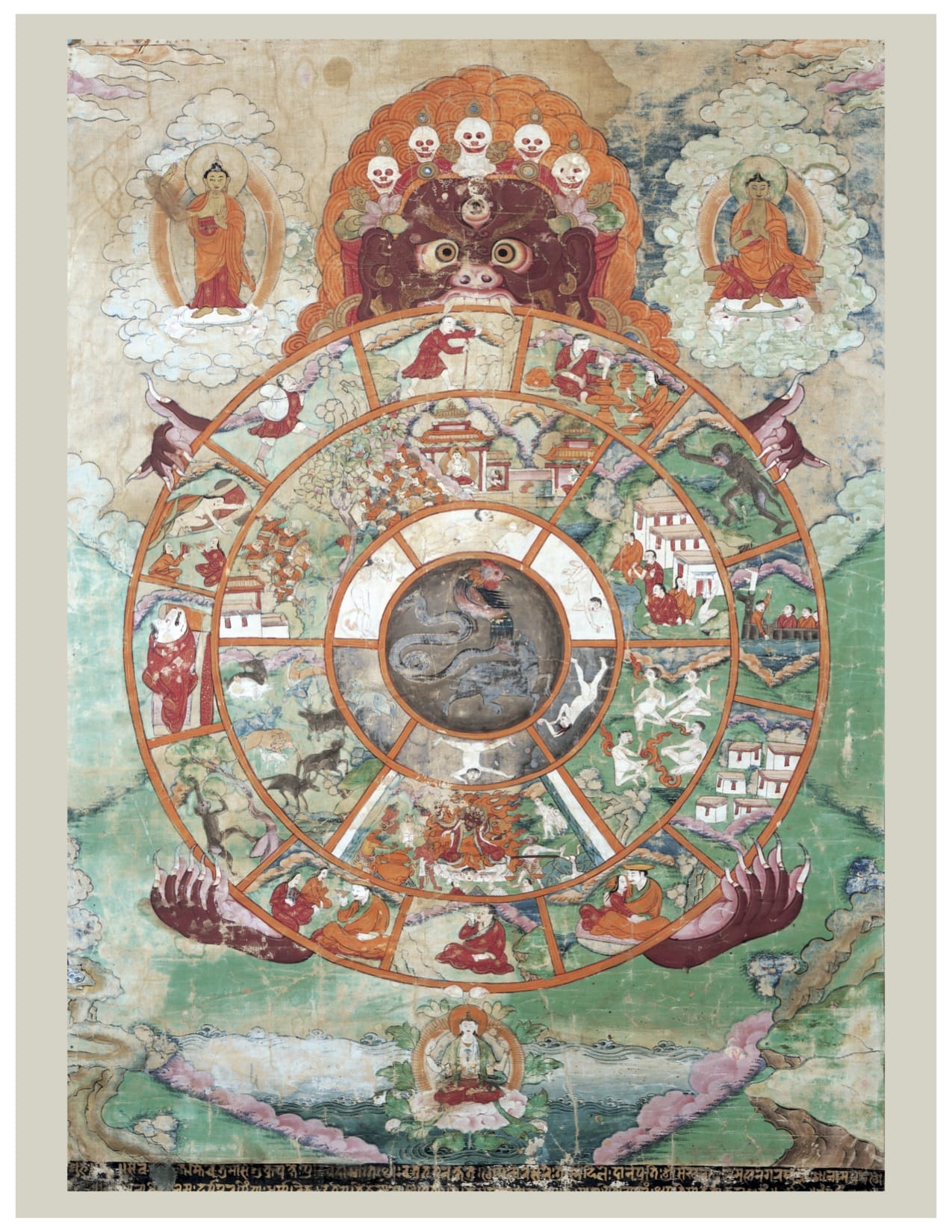

Shakyamuni Buddha–Jataka (detail). Tibet, 1700–1799, Collection of Rubin Museum of Art (acc.# P1996.12.6)

Everyone takes refuge in something. Often it’s in relationships, locations, or activities that offer the body or mind a sense of security and protection. Even neurotic or unhealthy habits—like eating too much chocolate or giggling compulsively—can function as a protective shield to ward off feelings of anxiety or vulnerability.

Ask yourself, “Where do I look for happiness? Where do I seek security and comfort?” In love, in social status, or in the stock market? Our car may break down, our company may declare bankruptcy, or our partner may walk out. Our perfect health will surely deteriorate and a loved one will surely die. The stock market goes up and down; reputations go up and down; health, wealth, and relationships—all these samsaric refuges go up and down. When we place our trust in them, our mind goes up and down like flags flapping in the wind.

One Frenchman told me that his own Tibetan teacher had discouraged students from ordination. This really surprised me. He explained that his teacher had said, “Most Westerners who put on Buddhist robes take refuge in their robes, not in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha.” I assured him that this was not limited to the West.

We live with a sense of lack that we long to fill. The monkey mind habitually tries to merge with something—particularly another person— in order to alleviate our pervasive sense of insufficiency. Yet samsaric refuges are inherently impermanent, and if we rely on permanence where none exists in the first place, then feelings of betrayal and anger compound the loss.

Emotions can also become refuges. Responding with anger and self-righteousness and looking for something to blame can become a habitual place to hide. If anger reassures your identity, you may return to that state for shelter, the same way someone else returns to their home. Perhaps your habit is to become overwhelmed by confusion and to ask others to come to your rescue. Chronic helplessness can be a refuge, a way of pulling back from the world and from your responsibilities. Before taking refuge in the three jewels, it’s helpful to know the refuges you already depend on, because this examination might really inspire you to turn in another direction.

Taking refuge doesn’t protect us from problems in the world. It doesn’t shield us from war, famine, illness, accidents, and other difficulties. Rather, it provides tools to transform obstacles into opportunities. We learn how to relate to difficulties in a new way, and this protects us from confusion and despair. Traffic jams do not disappear, but we might not respond by leaning on our horns or swearing. Illnesses may afflict us, but we might still greet the day with a joyful appreciation for being alive. Eventually we rely on the best parts of our being in order to protect ourselves from those neurotic tendencies that create dissatisfaction. This allows for living in the world with greater ease and without needing to withdraw into untrustworthy circumstances in order to feel protected.